Introduction

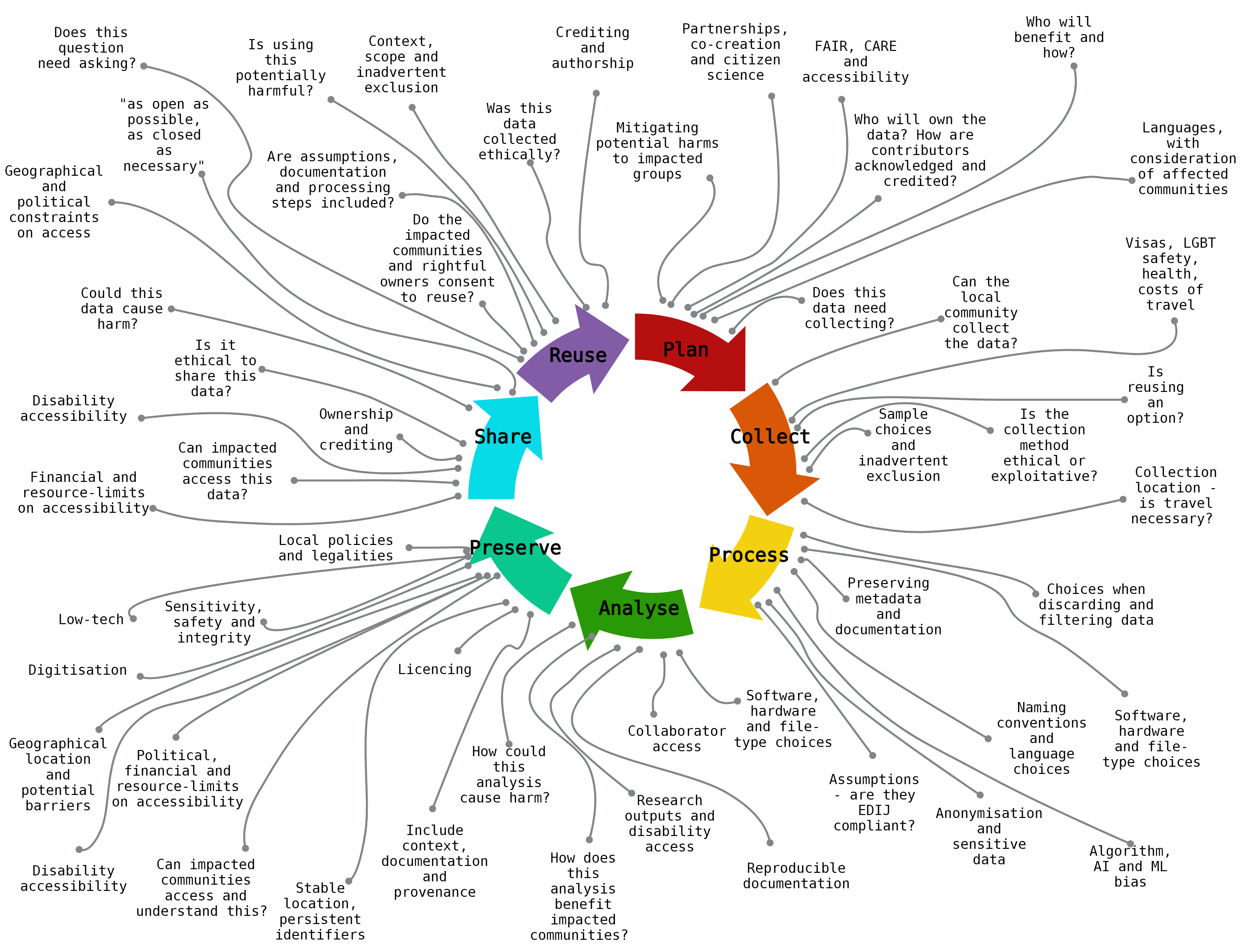

Data management is an integral aspect of all research, encompassing the effective handling of data collected and used in a study. Data can take many forms, and does not only include the numerical datasets most think of initially, but also physical samples and documents, images and even recordings of sound. The data cycle is composed of multiple stages which govern the process of collecting, using and sharing data in research; whilst each stage has some unique sub-tasks within it, there are also many overlapping aspects to each. Figure 1 illustrates the data cycle and the main tasks associated with each component of the cycle.

What are decolonisation and EDIJ?

Equity, Diversity, Inclusion and Justice (EDIJ) encompass a framework for building an inclusive environment and avoiding discrimination for individuals by taking into account different identities and how they impact the people within that environment. This can involve actively providing advantages for some groups in the same way a runner starting 50m behind another might need to begin a few seconds early to stand a fighting chance in a race. Equity is broadly defined as removing barriers, in order to level access for everyone. For example, providing reasonable adjustments for a disabled employee, to enable them to perform their role, would be equitable treatment, in that it allows them access to the same opportunities others have. Diversity is the concept of accounting for and celebrating the different identities and backgrounds of individuals, and building in measures to ensure those individuals have the ability to participate. For example, celebrating different religious festivals and providing cuisine from a variety of cultures in the workplace could contribute to diversity measures. Inclusion is the concept of ensuring the environment is welcoming to those of all identities and backgrounds, both by removing hostile elements and increasing the positive ones. For example, changing documentation to gender neutral terms would be an inclusive measure for women, transgender and non-binary people. Justice is the systemic process of rectifying past harm, exclusion and discrimination. It is important that EDIJ is not considered as just a box to tick, but an important aspect of life for those from historically excluded backgrounds.

Decolonisation is a related but separate concept. Whilst decolonisation has been a major topic in humanities, social science and arts fields, it is far more maligned in the sciences. Decolonisation links to the above ideas of EDIJ, but encompasses a much more systemic approach which requires undoing the harms of previous colonialism and challenging imperialist ideas and processes. Imperialism’s impacts are still felt today in economic, social and psychological ways, which requires restructuring of societal norms in order to rectify. This process necessitates consultations with those who have been harmed by colonialism, and also the provision of reparations, in addition to constant review and rectification of systems which still embody those colonial ideals within society.

Clearly, these are concepts of importance to society more widely, but many researchers in the sciences struggle to see the relevance of EDIJ and decolonisation within their field, often citing that ‘science is objective’ and focuses on ‘facts’, meaning these problems simply don’t impact their research. It is a central tenet of these concepts to understand that the world is not a meritocracy, and that the ‘best’ do not simply rise to the top of a field – EDIJ and decolonisation seek to mitigate this problem, which in theory will lead to better science and research overall. However, the more important consideration with reference to these ideas is the fact that ethics are key to science, and indeed science without ethics is simply not science. This ethical dimension includes the application of EDIJ and decolonising with respect to those working in the scientific research space but also those outside of that sphere, as they are impacted by the research conducted in other ways. Especially in the biosciences, it is vital to perform research in an ethical manner, and global justice, avoidance of exploitation and increasing participation in science are all key ideals of EDIJ and decolonisation work. Nature has produced a series of articles exploring decolonisation in science and research, with exploration of important concepts and interviews with researchers working in this area (Nature Decolonising Science Toolkit).

Accessibility is a crucial related concept, which is essential to FAIR data management. However, often the concept of accessibility is interpreted in a manner more akin to availability in terms of data management. Many researchers believe that provided they make their data available in an open access repository or journal, they are thus making it accessible – this is not the case. A nice illustration of the difference can be made using a quote from Douglas Adam’s ‘A Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy’ – when the plans for Arthur Dent’s house to be demolished to build a new highway are ‘made available’ they are located in a dark cellar with no stairs, placed ‘in the bottom of a locked filing cabinet stuck in a disused lavatory with a sign on the door saying “Beware of the leopard”’. Arthur theoretically had access to the plans (they were available), but in reality could not view them without surmounting significant difficulties and obstacles (they were not accessible). It is vital to understand the difference between simply placing data in an open access location and making it truly accessible to those who might want or need to view or use it – truly accessible data has the barriers removed.

Why should you consider EDIJ and decolonisation in your data management strategy?

First and foremost, these frameworks should be considered from the perspective of the ethics of the research project – ethics is integral to good science and without ethical standards, the science becomes liable to inherent problems with bias. Whilst ethics encompasses far more than just EDIJ and decolonisation, both are essential for ethical data collection and management.

Inclusion of researchers from impacted groups, whether they be locals of a study region or people with a specific medical condition or disability, enables the generation of more relevant research questions and higher impact research with more meaningful benefits. Their knowledge and lived experience means they can view research plans and collected datasets with the correct contextual information to draw out useful conclusions. As such, partnerships with groups that have historically been excluded from the entire research process should be an important part of designing a study and a data management plan.

Diversity within research teams improves research, with more novel ideas and creative approaches to research questions (Trisos et al., 2021). Science can only benefit from improved access from a wider range of people with different viewpoints and experiences, so even when data has already been collected, ensuring it is disseminated in a way which allows wide-ranging accessibility can lead to new discoveries. Those from different academic or professional backgrounds having access to data they can understand and use means policy makers can make the best and most impactful decisions, and collaboration opportunities across disciplines can be opened up. This can in turn open doors to a wider range of funding sources for further projects. Marx’s 2023 article summarises some benefits and considerations for data accessibility in the biosciences and the fundamental role this data sharing plays in science (Marx, 2023).

Consideration of EDIJ and the concept of partnerships in data collection and research are now a central tenant of many funding bodies’ application processes; embedding these ideals into proposals is the best way to ensure competitive funding pitches are produced. The Wellcome Trust released a short editorial following the Global Forum for Bioethics in Research consultation on data sharing and biobanking, which summarises some of the key issues they believe research teams should consider going forward (Bull and Bhagwandin). Likewise, open research and reproducibility are also considered vital components of any grant proposal, so understanding how to improve the accessibility of the data involved means this can be conveyed clearly and effectively in said proposals.

Improving accessibility of research and data for marginalised groups is also key to improving trust in science more generally. Many people feel suspicious of much scientific research, particularly those who have suffered discrimination or other consequences via imperialist science in the past. Improving access to the underlying data behind decisions, and the manner in which it is collected, shared and used, means that these groups can have increased confidence in research. In the same vein, accessibility of data to other researchers means increased data integrity and the avoidance of misconduct is easier to achieve.

Overall, there are many important benefits to improving accessibility and complying with these frameworks in research and data management. This article will explain what the main considerations are for embedding EDIJ and decolonisation within data management at each stage of the data cycle, before providing three examples of how to apply these frameworks to different disciplines of biological research. This is very much a starting point resource to begin implementing these ideas into future data management practice, with some valuable resources signposted for researchers to use in this endeavour.

EDIJ, decolonisation and the data cycle

Each stage of the data cycle requires consideration of multiple aspects of EDIJ and decolonisation. Whilst there are overlaps between them, the below provides a framework for ideas and questions to address within each component stage.

Planning

Realistically, planning is the most difficult stage to differentiate from all others, as the entire concept inherently encompasses the others within it. However, there are a number of key considerations which can best be considered while planning a data management strategy for a project. The first and most vital question to address is whether the data need collecting at all; is there a need for this piece of research and if so, does the data for it already exist? Who will benefit from this research and how? Is there potential to cause harm with this data and if so, how is that going to be mitigated? The CARE principles of Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility and Ethics were established by the International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group with the aim of ensuring data ethics are upheld and potential harms considered, as well as bringing new considerations to data ownership (GIDA-Global website); the CARE principles should be considered carefully when planning any project requiring use of human or ecological data.

Next to consider is the data itself – who will own this data and how will contributors be acknowledged or credited? Who is accountable for the study and the data in terms of both security and integrity? Do the communities being researched have the correct degree of sovereignty over the data? Can they make decisions and will those be honoured? Building collaborations with researchers in lower-income countries is essential for a more globally equitable scientific system, but these relationships must be truly collaborative and not simply extractive, and should give credit for the contributions, including allocation of appropriate financial resources for the project (Armenteras, 2021; Gewin, 2022). It is vital to consult with impacted groups and listen to their concerns whilst planning the project, to ensure ongoing trust from the communities being impacted and the wider public. Establishing a partnership model for the data is a far more ethical approach to data management than a participant model, where research subjects are not part of the actual team running the study.

Consider whether this data be collected using a citizen science approach? Are there alternative knowledge sources, such as verbal histories, indigenous science or local arts, which could assist in this project or even supplant the planned data collection? Data includes a far wider range of resources than are routinely considered within the sciences, and often these alternative sources can provide rich information and important context for the scientific ideas being explored (Trisos et al., 2021).

Communication strategies and storage for the data long term are explored in more detail below, but some broader aspects more neatly fit into the planning stage. The language of storage and dissemination is a vital consideration for accessibility – if impacted communities cannot understand the resources you gather, it is not accessible no matter how ‘open access’ the repository is. Ensure that data is available in all relevant languages for impacted communities, as well as considering how best to make them accessible to those with disabilities. For example, is it possible to read the data with a screen reader? Does it use accessible fonts, descriptors and colour choices? Does it include data that relies on a sense some of the community do not have, such as hearing or vision? If so, how can you make this data available to those people? The 7 principles of universal design (Universal Design website), although conceived for use in physical spaces, can be an ideal starting point for implementing disability access principles into a data management plan.

Collecting

Within the collection stage, the first question to ask is always whether reusing other data is an option. This is covered in more detail in the last stage of the cycle, but is important to address here before moving on to additional concerns.

Consider the location of data collection – is field work required? If so, where is the appropriate location to avoid damaging local communities and the wider environment? Is there a more ethical option which could be chosen? If travel is required, it is also vital to consider the researchers themselves at this point; there may be problems with visas, LGBT safety and health concerns or disabilities which may exclude certain members of the research team from participation in this process. It is then vital to assess whether this is justified by the importance of the sample being collected. It may be possible for the local community and/or researchers in situ to collect the data instead – if this is an option, it is often a much more ethical approach which provides opportunities for researchers who may have historically been excluded from such projects and even suffered as a result of them. It is vital to ensure collection methods are not exploiting the local people and the wider area in any way.

It is also of huge importance to consider sampling choices and whether any data collection methods may inadvertently exclude individuals in a way that makes the data less useful or more damaging. For example, writing a questionnaire which is difficult for those with learning disability or neurodivergence to fill in will exclude those groups at a higher rate than others, giving potentially biased findings. Providing only male and female as options on a medical form may miss other marginalised genders and intersex conditions, resulting in flawed conclusions. This can impact on the relevance of things like genomic datasets and epidemiological studies, but can also damage experimental work if variables like the sex of an animal model or cell line origin are not taken into account.

Data security after collection is also a major consideration, particularly for any studies involving human participants and health data. Ensuring detailed documentation is kept for all protocols and procedures is also vital for identifying any flaws in the methodology, as well as providing explanatory context and details for those unfamiliar with the research, increasing accessibility to the wider community.

Processing

In this stage, it is critical to question choices made when filtering and discarding data points; are these choices compliant with EDIJ and decolonisation or are they relying on biased or problematic assumptions? Are they potentially damaging to certain groups? Particularly if AI or ML algorithms are being applied, considering the bias in those processes is vital. Proper documentation, providing clear definitions and relationships, and ensuring metadata are fully preserved, are all key components of maintaining accessibility and avoiding your assumptions having downstream impacts which cannot be reversed by going back to the original dataset. Ensuring any data relating to sensitive characteristics is anonymised is also a major aspect of this stage of the cycle. Finally, considering the software and hardware choices made for implementing this process is essential for providing accessible protocols that others can check and alter if issues are found with the analysis pipeline.

Analysing

Many of the issues above overlap with the analysis stage, particularly in relation to assumptions, algorithm use, reproducible documentation and software/hardware choices. Additionally, ensuring collaborators have access to the data at this stage, especially those from communities impacted by the research, is important. Consideration of the potential benefits and harms of this analysis is a vital aspect of ethical research and especially important in the analysis stage. Confirming that research outputs are able to be accessed by researchers and other impacted groups with disabilities is also a major concern at this stage of the cycle.

Preserving

Local policies, licencing agreements and other potential barriers are all important considerations for equitable access to the data for other researchers and impacted communities. Ensure cultural considerations regarding the storage and export of physical samples are considered, with consultation and approval from local teams on the most ethical way to preserve important specimens (Bull and Bhagwandin). Low tech solutions are generally preferable to anything involving more resources (financial, technical or expertise) for ensuring the most accessible data storage (Perkel, 2023). Consider digitisation if data is in a format that might make access for those not in close physical proximity to the data more viable (Trisos et al., 2021). The integrity and security of the preservation method are also key – do not use storage which relies on a host which may become obsolete downstream, and ensure persistent identifiers are used. Additionally, the preservation must ensure the right degree of protection for the data, with appropriate consideration of the sensitivity and potential harms of data which is too accessible. Inclusion of appropriate documentation, provenance information and context, with consultation on this with impacted groups, is also vital (Trisos et al., 2021). The communities impacted need to be able to understand the data in order for it to be accessible, so the manner in which this information is supplied must be carefully considered.

Sharing

Again, within this stage it is vital to reassess whether the data collected, now that analysis has been done, has the potential to cause harm. The earlier stages may have revealed unanticipated issues which mean that the answer to this question has changed and the data management plan requires reconsideration. Sharing data is not always the ethical choice, both for harm avoidance but also for any data involving health and other sensitive topics, where it may be best overall to keep data private. Even when data has been anonymised, it still may be possible to identify some individuals with the provided details. Data access should be ‘as open as possible, as closed as necessary’ (ref), which sometimes means open access is not the most ethical choice (Trisos et al., 2021). Controversy surrounding the publication of the genome the widely used HeLa cell without the consent of Henrietta Lacks’ remaining family highlights one of the issues here; researchers need to consider not just the scientific utility of sharing data, but also the privacy and rights of those impacted, even where they are not the original source of the data itself. Future generations can be impacted by data collected now in myriad ways and ethical considerations should always eclipse any other benefits the data being shared might have.

Consider whether impacted communities have access to the data relating to them (Bull and Bhagwandin). Is it in a language they can understand? Is it on a repository they can access (geographic, financial and political concerns all impact this)? Can disabled people access the data in an equitable way and if not, how will that be rectified? Ownership of data is also crucial here – ensuring that any communities and individuals involved receive the correct recognition of their contributions and have the ability to remove consent for sharing is vital for ethical data management (Trisos et al., 2021).

Reusing

The final stage of the cycle is reuse and brings in many additional complications when considering EDIJ and decolonisation, due to the ways in which science and medical research were done in the past and the wide-ranging harms which were perpetrated in generating past datasets. Even now, many datasets are not collected in an ethical and inclusive way, meaning even a contemporaneous study can generate data which does not comply with the ideals of EDIJ and decolonisation.

Consider whether the data you propose to utilise was collected in an ethical manner. If exploitation or unethical collection methods were used, it is unlikely to be justifiable to use the data for your project. If the full context and scope of this data, and any assumptions and processing steps, are not included in the documentation, and thus the ethics of collection cannot be established, it would be unlikely this data can be used without potential harms being caused.

Ensure the original authors are properly credited and acknowledged, including acknowledgement of the contributions of individuals or groups who were excluded from recognition at the time but clearly contributed to the data (Bull and Bhagwandin). Do the groups impacted by the data consent to its use and the purposes of the study proposed? Have any exclusions from the study participants and biases in sample choices been accounted for? Is a land acknowledgement appropriate when using this data?

Not every question that can be asked should be asked; as Ian Malcolm of Jurassic Park once said ‘they were so preoccupied with whether they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should’. If the data and study are potentially causing damage and not providing benefit for those most impacted, it is not compatible with EDIJ or decolonisation ideals to collect or use the data as proposed. In these cases, even if data is potentially available which could be used, it is not be good scientific practice to use that data in any form. Some questions simply cannot be answered whilst maintaining ethical standards, and in these cases, it is not acceptable to discard ethics in favour of research.

How would this apply to different sub-disciplines?

Within different sub-disciplines of biology and health research, different issues and considerations come into play. Here we briefly describe some of these for three different research fields, but these are by no means an exhaustive list.

Neglected Tropical Disease research

Research into the Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) has historically involved injustice and exclusion. Indeed, the field of tropical medicine was founded due to imperialist enterprise and is inherently intertwined with the colonialist project (Bump and Aniebo, 2022). Nowadays the field is far more focussed on the well-being of the local communities impacted by these diseases and there is a strong drive to increase participation of both local researchers and patients from endemic areas.

Consideration of the CARE principles is a key aspect of this work, as is the inclusion of locals in the early stages of project planning – defining research questions, conceiving collection processes and designing and implementing analysis protocols (Bull and Bhagwandin). These groups possess the knowledge and experience to know the most important and impactful questions to ask, and establishing partnerships with local researchers helps to enable this process, whilst also providing reparations for past injustices and exclusion from the research community. Locals are also best placed to understand the wider context of the data being collected, and can provide valuable input on variables such as cultural and environmental factors which might otherwise not be considered by researchers from elsewhere; non-traditional knowledge sources are often disregarded by scientists, but can give contextual information which in some cases resolves a missing aspect of a disease mechanism of spread. The avoidance of a ‘parachute science’ approach is essential to any EDIJ and decolonisation plan for research, but is also essential for successful research itself.

The process of data generation, storage and dissemination itself must involve clear information for participants, enabling them to fully consent to the intended uses – this can only be done if this information is communicated clearly and effectively in a language understood by these communities and this extends to any dissemination and publication of the data. Language use on forms and documentation also needs to be considered; are there terms being used which are perpetuating colonial ideals (e.g. species or disease names)? Do disease names use geographic or ethnic names which could bring problematic connotations or stigma to those communities? Are there local terms which could be used in place of English ones? Access to data repositories can differ between regions globally, with NTD-affected regions often also lacking financial resources and access to certain types of hardware and software. Ensure these aspects are accounted for when planning for preservation, to maintain accessibility for those most impacted by the dataset and subsequent work – try to be as low tech as possible in the data management strategy. Projects like Africa Connect, AfrikArXiv and Aphrike Research seek to improve accessibility to research and data for researchers within Africa and similar projects exist for other historically excluded regions; consider contacting them and implementing their advice on how to ensure your data is accessible to the communities they are serving.

Collection methods cannot be exploitative in any way (Bull and Bhagwandin), and this can make reuse of historic data in tropical medicine somewhat problematic. Ultimately this question needs to be addressed on an individual project basis, but future data generation must also consider the sensitivity and potential harm of sharing certain datasets, especially where third parties such as profit-generating companies may benefit. Participants and co-researchers in the region must also be provided with appropriate credit and ownership of the data (Bull and Bhagwandin), and authorship of any resulting publications, and they must retain the right to remove their data at any point in the data cycle. Consider also how certain variables, such as gender, sexuality and ethnicity, are being measured and recorded – is there a possibility of inadvertent exclusion of certain groups due to this? Does the terminology used mean the same as the common meaning in English or are definitions different between different cultures?

Ecology and Conservation research

Ecology and conservation work also provides a useful way to consider EDIJ and decolonisation in a field which generally does not include many human participants directly in the research being conducted; these concepts are still highly applicable here however. Again, the key question is always whether the data collected has the potential to do harm, either via the original research proposal or subsequent work if the data is shared. For example, the knowledge of a species of plant with significant medicinal benefits can cause damage to a local ecosystem and the people living in the area if it becomes overexploited by third parties for financial gain, so the benefits and risks of open access to the full data need to be examined carefully in these sorts of scenarios.

Naming conventions, as with NTDs, are an important consideration for this type of work – species names and categorisation may differ between researchers from other countries and the local community. This knowledge can provide valuable insight into aspects of ecosystem function and species biology, but more importantly, using the local names and avoiding names with colonial connotations is a way to show respect and consideration to communities. For example, the classification of a species as a pest vs as in need of protected status is important to consider in order to establish conservation plans which will be more likely to succeed long term; engagement with local communities is essential for the success of these types of projects. Conservation work must not override the individuals living with the consequences of those measures and their concerns – liaising with local communities and researchers from those communities can help prevent conflict arising between researcher’s motivations and those of the impacted communities. Again, the partnership model is a vital aspect of conducting research in the field, to avoid ‘parachute science’ which will cause damage and have little beneficial long-term impact. Land acknowledgements can be one valuable way to show appropriate respect to the inhabitants of the region a study was performed in (Bull and Bhagwandin; Trisos et al., 2021).

The trust of local communities in the science being done is important for the ethical collection of data (Bull and Bhagwandin; Trisos et al., 2021) and can sometimes be encouraged via approaches such as citizen science for data collection processes; this should be considered as a viable option when designing a data management plan. Data collection by local people, whether researchers or the general public, can also reduce potential harms to researchers elsewhere, who may suffer hardship in travelling to some regions. For example, LGBTQ+ researchers or those with health problems can find travel inaccessible or damaging to their wellbeing, so involving local people with the research process can alleviate pressure on these individuals and benefit both sides of the collaboration. Non-traditional knowledge sources, often disregarded in scientific research, can likewise provide essential context which can allow research questions to be more accurately addressed (Trisos et al., 2021); working with local groups is often the only way to access this information.

Data collected needs to be stored and disseminated in an accessible way – local communities should be able to access data collected in their area, as they are the most likely to be impacted by any research conducted. Therefore it is vital to ensure that the choices of repository, software and hardware for analysis are able to be accessed even from regions with limited resources (Bull and Bhagwandin; Trisos et al., 2021). Language choices should be made with the local community in mind; documentation, datasets and publications should all be disseminated in local languages to enable access for the communities involved. The reverse is also true – many concepts cannot be adequately conveyed in English, but local languages can capture that important nuance. Researchers designing studies and collecting data should ensure collection methods are considering these additional aspects and should include local language-speakers as members of the research team (Trisos et al., 2021).

For physical specimens, it is necessary to carefully consider physical location for storage, to ensure samples are not unnecessarily removed from their locale (Bull and Bhagwandin; Trisos et al., 2021); if removal is required, it should be done with the consent of community members, who may have a much stronger relationship to their ecological surroundings than the researchers. In many cultures, the natural environment has spiritual significance and it is important that this is respected appropriately by external researchers. The tuatara genome project (Gemmel et al, 2020) provides a good exemplar for work of this type, which necessitates the use of culturally important ecological resources; they supply their agreement template for high level consultation and co-ownership of the resulting data, for use in future genome sequencing projects.

Appropriate digitisation of samples should be done to ensure ongoing access for all, to allow a wide range of researchers to utilise the data to address different questions and ensure integrity is maintained. GBIF is one example of a project working towards this goal by building a database of disparate sources of ecological and other life-based data in an open access digital format. The data is controlled and owned by the creator, with crediting and tracking tools, and obligations on attribution of the original source by subsequent users (GBIF website).

Disability research

Genomic databases are an example of the way that research into disabilities can also cause harm to disabled people. Many disabled people do not support the aim of cure or eradication of their disability (Natri et al., 2023), but often researchers frame their work in this way, and this can be detrimental to the wellbeing of the people they purport to be helping. Genomic databases run the risk of providing data in support of eugenic ideas such as pre-natal testing (Natri et al., 2023), and could lead to problems for future generations, such as issues obtaining health insurance if this data becomes widely accessible to third parties. It is vital to listen to disabled people about the types of research they feel would benefit their community (Natri et al., 2023); developing a research culture which is inclusive for disabled people plays a major role in this, and as such the design of data management strategies and collection processes needs to be done with disability access in mind (Swenor and Rizzo). One example of this is exhibited in the collaborative development of a set of recommendations on autism genomics research, which included autistic researchers and experts in bioethics to establish guiding principles for the future of this type of work, with the wellbeing and priorities of autistic people at the forefront (Natri et al., 2023).

Data management strategies should carefully consider ownership concerns and issues around retraction of consent when planning data collection involving disabled people. Exploitation of disabled people must be avoided when planning data collection; often it is not possible to obtain informed consent from specific subsets of disabled communities, yet we frequently see consent being given to provide data for potentially harmful studies by parents and carers on behalf of disabled people, such as autistic children or those with learning disabilities (Natri et al., 2023). This is often not ethically acceptable, given the lack of ability to understand the use and future implications of the data being collected, and an inability to remove access to the data in the future.

The collection process needs to provide relevant accessibility accommodations for both researchers and participants to enable data collection to be a fully inclusive process, and those providing information on their lived experiences need to be compensated appropriately for their time, in the same way other experts would be. Reusing data can prove problematic due to the vast history of ableism in medical research, which resulted in many unethical research studies being conducted in the past (Natri et al., 2023); whether or not a dataset can be used ethically is a question that must be addressed for each individual dataset and study.

Again, language choices are important when collecting and documenting data. Defining certain traits as ‘symptoms’ or ‘deficits’, referring to conditions using inhumane language and framing questions and aims around the concepts of disease and cure can cause huge hurt and distress to disabled communities. Data and documentation should be provided in a manner which allows the impacted communities to access it; for example, if research is being done into a learning disability, this means providing the data in a format which can be understood by people with that learning disability. Likewise, if data is focussed on vision impairments, then sharing this data in a way which allows screen reader function is essential. Using the 7 principles of universal design (Universal Design website: The 7 Principles) can be an ideal way to begin implementing disability access principles into your data management processes; whilst the specifics of each principle may not be applicable to every data type, they provide a set of grounding ideas to begin to consider how to make data accessible in an equitable way for all, not only for the disabled community.

Summary of key considerations for EDIJ and decolonisation in data management

In summary, EDIJ and decolonisation are necessary considerations for conducting ethical research and data management; implementing them within data management plans can bring benefits for individual researchers, wider society and historically excluded groups, and science as a whole. The main consideration for any data management plan must always be ‘what are the potential benefits and harms of this research?’ Ask who is benefiting from this data and how. Are CARE principles being followed?

Other key follow-up considerations which apply to all disciplines include:

- Is the data being collected (or was the data collected, for reuse) in an ethical way? Will exploitation be a part of this process (or was it)?

- Have impacted communities been consulted? Were any concerns listened to and addressed?

- Who will own the data? Who should own the data? Do those most impacted have sovereignty and agency around choices made?

- Who should be able to access this data? Can they access it? Consider impacted groups, other researchers, the general public, disabled people, languages and resource barriers when answering these questions, but also address whether this data should be accessible – is it covering sensitive topics or could open access cause harm in some way?

- Is the research process a partnership or a participation model?

- Have assumptions or exclusions (both purposeful and inadvertent) changed the data in a way that biases against EDIJ and decolonisation principles?

Additional considerations or nuance apply to different subfields and data types, and this article provides a jumping-off point for creating an inclusive and decolonised data management plan, using the resources provided.

References

AfricArXiv website: https://africarxiv.pubpub.org/decolonising-scientific-writing-for-africa

Africa Connect website: https://africaconnect3.net/the-road-towards-a-more-prosperous-future-education-and-training-sdg-8/

Afrike research website: https://www.aphrikeresearch.com/

Armenteras, D. Guidelines for healthy global scientific collaborations. Nat Ecol Evol 5, 1193–1194 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01496-y

Bull, S., Bhagwandin, N., (2020). The Ethics of Data Sharing and Biobanking in Health Research [version 1; peer review: not peer reviewed]. Wellcome Open Research.

Bump JB, Aniebo I (2022) Colonialism, malaria, and the decolonization of global health. PLOS Glob Public Health 2(9): e0000936. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000936

Gemmell, N.J., Rutherford, K., Prost, S. et al. The tuatara genome reveals ancient features of amniote evolution. Nature 584, 403–409 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2561-9

Gewin, V. (2022). Nature 612: 178 doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-03822-1

GBIF website. https://www.gbif.org/health

GIDA Global website: https://www.gida-global.org/care

Marx, V. To share is to be a scientist. Nat Methods 20, 984–989 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-023-01927-7

Natri et al. (2023). Ethical Challenges in Autism Genomics: Recommendations for Researchers. European Journal of Medical Genetics 66(9): 104810 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmg.2023.104810

Nature Decolonising Science Toolkit: https://www.nature.com/collections/giaahdbacj

Perkey, J.M. (2023). How to make your scientific data accessible, discoverable and useful. Nature 618, 1098-1099 doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-01929-7

Swenor,B., Rizzo, J.R., Open access to research can close gaps for people with disabilities. Stat News Online. https://www.statnews.com/2022/09/06/open-access-to-research-can-close-gaps-for-people-with-disabilities/

Trisos, C.H., Auerbach, J. & Katti, M. Decoloniality and anti-oppressive practices for a more ethical ecology. Nat Ecol Evol 5, 1205–1212 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01460-w

Universal Design website: https://universaldesign.ie/what-is-universal-design/definition-and-overview/

RDM Kit: Data Life Cycle. https://rdmkit.elixir-europe.org/data_life_cycle

Interviewees and contributors

- Francis Crawley

- Sara El-Gebali

- Allyson Lister

- Kyle Copas

- Ebuka Ezeike

- Jo Havemann

- Arthur Nathaniel Mwang’onda